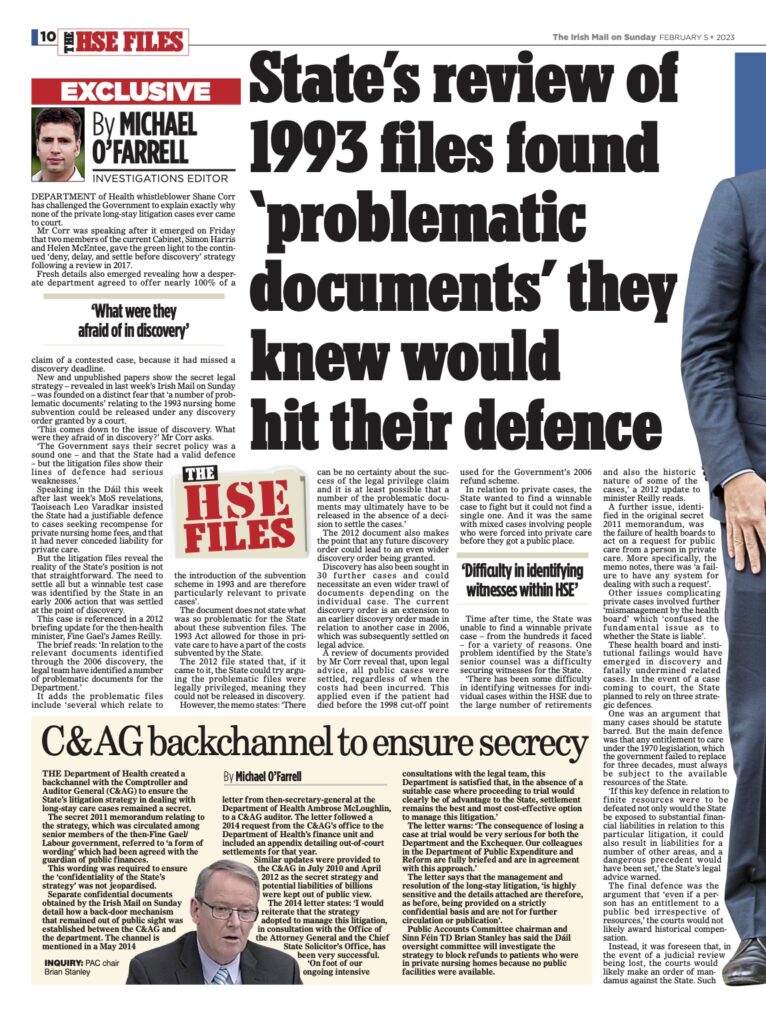

Successive taoisigh and health ministers – including current Cabinet members – agreed a secret plan to hide the true scale of the State’s liability for illegal nursing home charges to prevent massive payouts, confidential Government records reveal.

The top-secret files confirm the State faced the prospect of a €12bn liability in compensation for hundreds of thousands of families who were wrongly charged for the care of their loved ones over a 30-year period. In many cases, vulnerable families suffered extreme financial hardship as a result of the illegal charges.

Documents obtained reveal how successive senior government leaders from Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael, Labour and the Progressive Democrats acted in unison to thwart repayments worth billions to those wrongly charged.

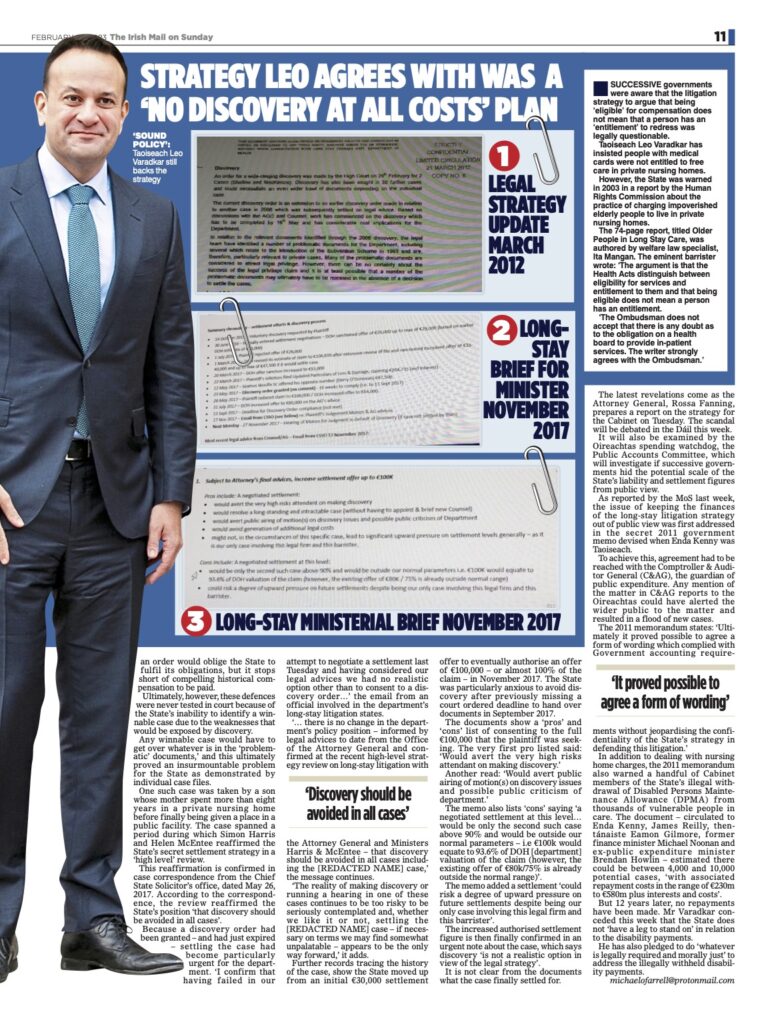

They did this by backing a covert legal strategy designed to cover up the fact that the State knew it could not win hundreds of cases – some of which are still outstanding – taken by families affected by the scandal.

As a result of this strategy, compensation was denied to anyone who did not have the resources to fight legal cases. The rest of the cases were all quietly settled by the State.

The strategy is outlined in a confidential and high-level government memorandum first prepared by the Department of Health in 2011.

Dated July 13, 2011, the memorandum is marked ‘SECRET’ and was restricted to just four government heads in addition to then-Health Minister James Reilly and former attorney general Máire Whelan.

Included in the tight loop, were then-Taoiseach Enda Kenny, former tánaiste Eamon Gilmore, Michael Noonan the finance minister at the time, and ex-minister for public expenditure Brendan Howlin.

The strategy, which is still current, was in turn reaffirmed while successive health ministers, including current Taoiseach Leo Varadkar and current Justice Minister Simon Harris, were in office. A new attorney general, Séamus Woulfe, who is now a Supreme Court judge, was also aware of the controversial strategy.

The memorandum and accompanying files were provided in a protected disclosure by Department of Health whistleblower Shane Corr.

On Saturday Mr Corr, who has been to the fore in exposing numerous public interest scandals, said he was ‘shocked by the scale of the cover up’. ‘Vulnerable people in the care of the State were wrongly stripped of their assets and in some cases their families disinherited,’ he said.

‘Many would have been denied that one last family holiday or the funeral that they saved for, so that political promises could be funded elsewhere.’

The files make it clear complete secrecy was essential if the plan was to succeed.

‘Confidentiality has been a central element of the legal strategy,’ one memorandum reads.

The aim of this strategy, which was subsequently passed down and reaffirmed by successive governments up to the present day, was that none of the cases taken by hundreds of families could proceed because the State did not believe it could win.

The plan was to drag out and prolong cases before settling, but only at the point of discovery when the State would be ordered by the courts to provide documents to other parties.

A 2011 document stated: ‘The fear is that if details of the cases, the legal strategy and settlements were to gain a high public profile, it would spark a large number of claims. It is therefore important that this litigation is handled with extreme care, discretion and confidentiality.

‘The liability to which the State could, potentially, be exposed if a case were to be lost and set an adverse precedent would be very substantial indeed.’

According to the files, this liability could have amounted to as much as €12bn, an estimate made up of two separate categories of cases.

The first was ‘a potential exposure of €5bn’ relating to up to 250,000 patients with medical cards who had been improperly charged in public nursing homes since 1976.

The second category of claim involved residents who had no choice but to pay for private nursing homes because no public places were available. According to government estimates, these claims represented ‘a potential exposure of approximately €7bn in respect of existing and potential private cases’.

Several examples of both categories of cases have been documented in more than 1,000 complaints to the Ombudsman over the years.

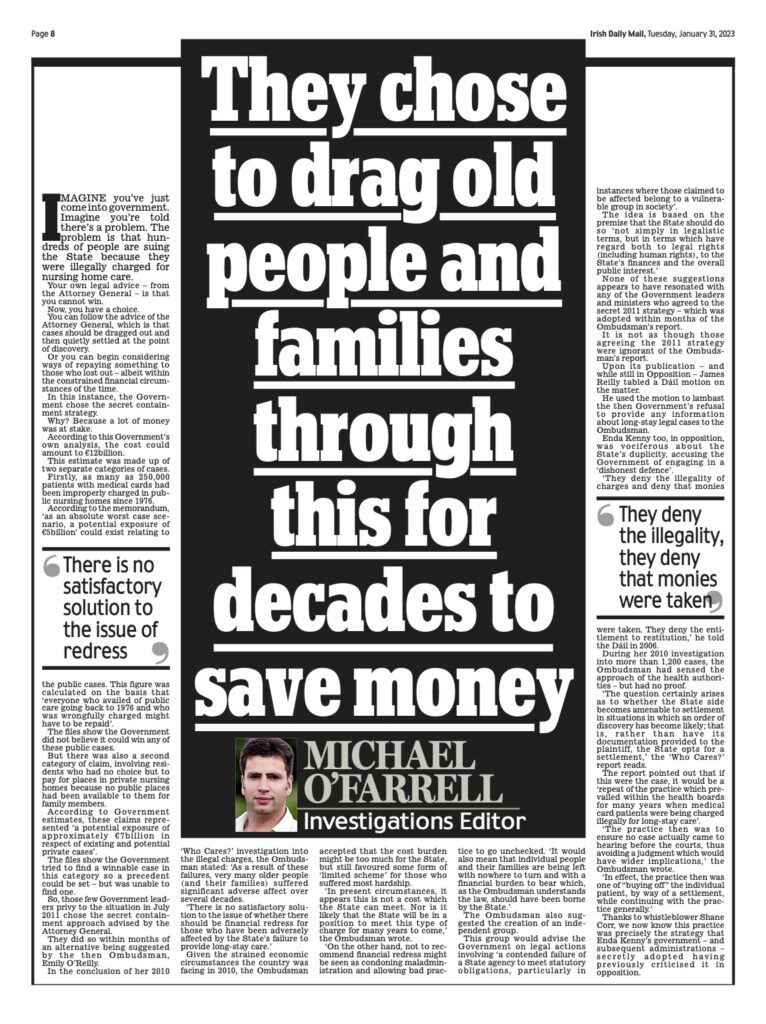

In 2010, the Ombudsman published a report entitled ‘Who Cares?’ into the illegal charging scandal. The report reads: ‘We now know that the department and the health boards were in no real doubt as to what the law provided and that they persisted with an illegal charging regime because of, amongst other things, the need to maintain an important source of funding.’

The report goes on to conclude that the ‘State agencies concerned have displayed intransigence, lack of transparency and accountability as well as a very poor sense of the public interest’.

‘At the administrative and institutional level, the continuation over such a long period of such unacceptable practices suggests inflexibility, non-responsiveness and a reluctance to face reality. It also suggests, at times, a disregard for the law.’

According to the files obtained by the MoS, the government agreed its secret containment strategy just a year after the critical Ombudsman report. They also reveal how the government ensured the cost of any settlements – and the size of the potential liability it faced – would not be publicly reported by its spending watchdog. To achieve this, agreement had to be reached with the Comptroller & Auditor General (C&AG). Any mention of the matter in C&AG reports to the Oireachtas could have alerted the wider public to the matter and results in a flood of new cases. ‘Ultimately it proved possible to agree a form of wording which complied with government accounting requirements without jeopardising the confidentiality of the State’s strategy in defending this litigation,’ the memorandum states.

Further confidential files confirm successive administrations continued the containment policy, monitoring developments closely as some cases were quietly settled, while others were discontinued.

By 2012, a confidential briefing for Minister Reilly showed that, of the 510 cases launched against the State, just 340 remained active.

The document warned: ‘There has been a marked increase in activity levels relating to existing cases over recent months.’

It also reported: ‘The overall increase in activity gives rise to some concern regarding the possible emergence of further cases.’

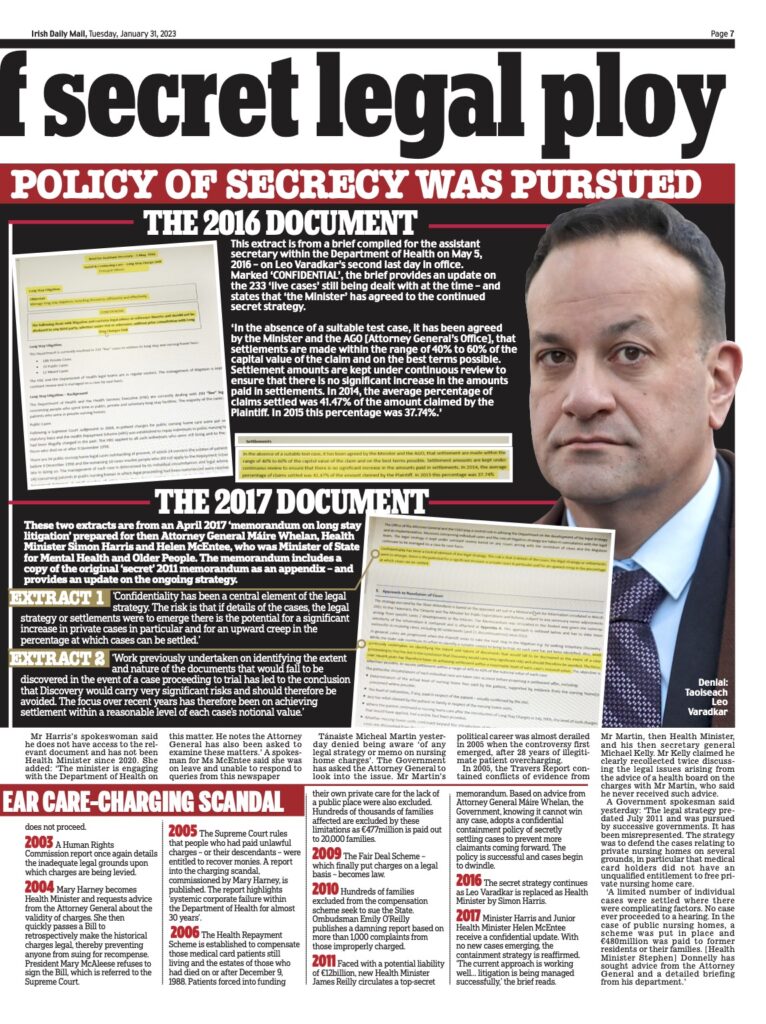

In May 2016, as Leo Varadkar was succeeded by Simon Harris as health minister, a brief prepared within the Department of Health confirmed the number of live cases had dropped to 233, with none launched since 2013.

‘The number of cases each year has steadily decreased which would indicate that the litigation is being successfully managed,’ it reads.

The brief also confirms the government’s policy remained one of settling cases, at the point of discovery, for between 40% to 60% of the claim value. It also showed the Government was able to successfully have a number of cases discontinued by simply writing to the solicitors concerned with a request that the litigation be dropped.

In April 2017, a further update was provided for then-Health Minister Simon Harris and Helen McEntee who was minister of state for mental health and older people. At this point, 220 live cases remained unresolved and – with no new cases emerging – the strategy remained one of slowly settling.

‘Discovery would carry very significant risks and should therefore be avoided,’ the 2017 brief reads.

The document adds the original 2011 approach, ‘has to date been successful in resolving cases including 80 settlements [and 21 discontinuations] since 2013.’

By 2017 these settlements had reached at least €2.6m, the briefing reveals.

‘The current approach is working well… litigation is being managed successfully,’ it adds.

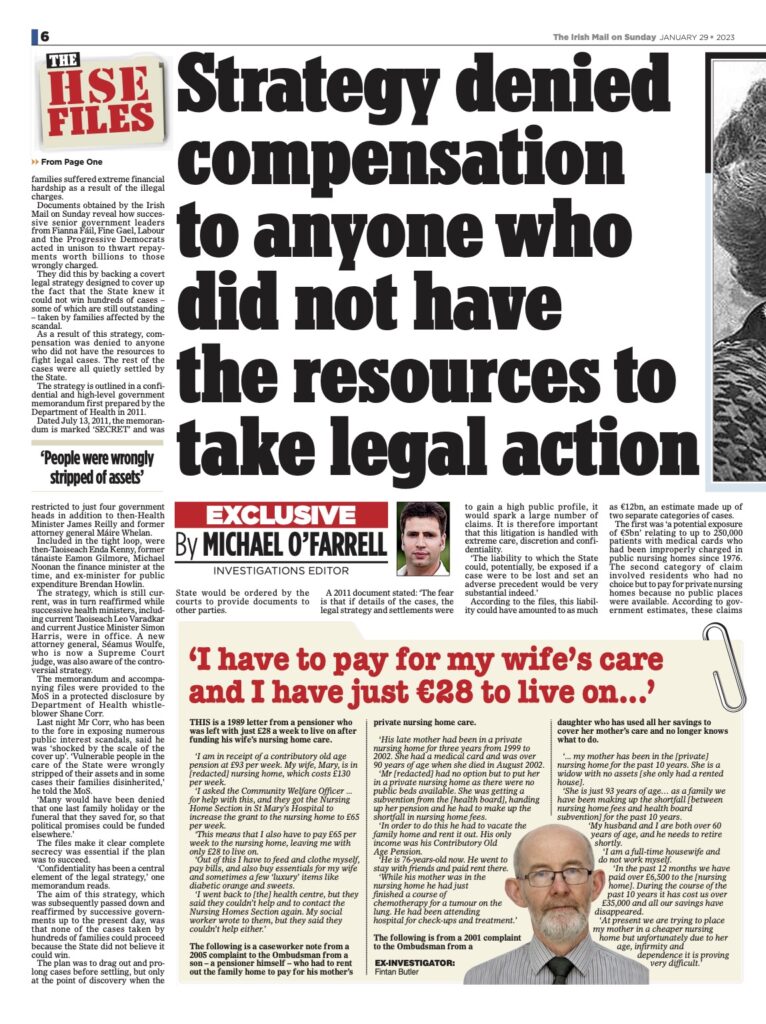

Fintan Butler, a former senior investigator for the Ombudsman’s office, said families who did not have recourse to legal resources were ignored as a result of the secret strategy.

Mr Butler said: ‘The consequence of the department’s strategy is that only those people who initiate legal action, and who have the patience and the resolve to pursue the case, will get any level of compensation.’

Before retiring, Mr Butler was centrally involved in investigating and compiling the 2010 Ombudsman’s report into the legal charges scandal. He was later an adviser to the European Ombudsman in Strasbourg from 2013 before he retired in October 2018.

He said: ‘Only a small minority of people, and their families, have the knowledge, the confidence and the legal support to initiate court action. The vast majority of the people adversely affected have not, and will not, take court action. They will not get any compensation. Clearly, the department’s strategy of containment does work.’

Mr Butler added that the practice of secretly settling cases with public resources, ‘suggests a huge failure in governmental transparency and accountability’.

‘From the documents acquired by the Mail on Sunday, we now know that 80 cases were settled between 2013 and 2016 at a cost of €2.6m. But this kind of information is not being published. It seems that the Dáil and Seanad are not being informed… and that questions raised at Oireachtas committees are not answered.’ When contacted in relation to the State’s legal strategy, the Departments of the Taoiseach, Finance, Public Expenditure and Reform and the Office of the Attorney General all directed our queries to the Department of Health. The Department of Health said: ‘The department does not comment on matters pertaining to litigation.’

Political leaders condemned illegal nursing home charges — and then devised secret strategy

Enda Kenny and James Reilly were not unfamiliar with the hardship and suffering caused by the illegal long-stay charges issue when they received a top-secret Government memorandum on Wednesday, July 13, 2011.

The memorandum detailed the State’s secret strategy of dragging out cases for as long as possible before settling quietly.

The strategy was adopted because the State knew it could not win, and billions were at stake.

Details of this strategy may have been new to Mr Kenny and Mr Reilly in July 2011 – but it was not the first time they had come across the litigation.

In fact both politicians, while previously in opposition, had railed against the possibility of the State engaging in such a tactic.

Just eight months prior to receiving the secret memo, Fine Gael were in opposition when a landmark report into the issue was published.

The ‘Who Cares?’ report by then Ombudsman Emily O’Reilly was based on more than 1,200 complaints spanning decades. During her investigation, the Ombudsman clashed with then health minister Mary Harney as her department refused to allow sight of the litigation details.

The Ombudsman’s report in November 2010, directly questioned the State’s motivation in defending hundreds of cases taken by families from whom money had been illegally taken.

The Ombudsman also noticed cases seemed to be inevitably settled just at the point of discovery. ‘The question certainly arises as to whether the State side becomes amenable to settlement in situations in which an order of discovery has become likely,’ the report states.

It also pointed out that, if indeed this was the case, it would be an unjustifiable repeat of the behaviour of the health boards – with the backing of the Department of Health – for decades.

‘The practice then was to ensure no case actually came to hearing before the courts thus avoiding a judgment which would have wider implications,’ the Ombudsman wrote.

‘In effect, the practice then was one of “buying off” the individual patient, by way of a settlement, while continuing with the practice generally.’

In opposition at the time, Mr Reilly was sufficiently concerned about the State’s behaviour to table a Dáil motion to discuss the Ombudsman’s report.

He told the Dáil at the time: ‘Knowing what one’s entitlements from the State are – and being able to count on being given one’s entitlements – is a basic right, a right that is more important in the case of vulnerable groups such as older people.

‘Fine Gael believes the law should be clear and that the State agencies should implement the law as it is, rather than as they would wish it to be if resources to meet statutory duties are not available, the legislation should be amended to reflect practice.’

Mr Reilly also addressed the litigation being taken by those seeking their rights.

‘At present, the State is defending in the High Court more than 300 legal actions taken by or on behalf of people who claim that their right to long-stay nursing home care has not been honoured,’ he told the Dáil. ‘To date, none of these cases has gone to hearing and judgment in the High Court.

‘The Ombudsman points out that this is surprising since many of the cases were commenced more than five years ago.’

Mr Reilly then raised a vital question: ‘Why, if the State maintained the cases had no merit, were they being settled? One can only wonder why, in these circumstances, the State is paying public money to people whose claims it believes to be without foundation,’ he asked Ms Harney.

‘Fine Gael believes the minister must clearly point out why and on what basis these cases were settled. Does the State consider that settling individual cases by way of compensation is less costly than the case going to a hearing in court? What about the hundreds of outstanding cases?’

Eight months later, now on the other side of the fence in government, Mr Reilly got his answer – and quickly changed his tune. Enda Kenny underwent a similar conversion. He too, in opposition, had been damning of the Fianna Fáil/Progressive Democrats’ handling of the legal cases. In February 2006, he told the Dáil that the government could not have it both ways – by privately defending cases for compensation before the courts, while publicly moving to legislate to make the previously unauthorised charges legal. At the time, Mr Kenny accused the Government of engaging in a ‘dishonest defence’.

‘In that defence, the Tánaiste [Ms Harney] and her co-defendants deny any liability,’ he said. ‘They deny the illegality of charges and deny that monies were taken. They deny the entitlement to restitution.’ But once in office – and privy to the secret strategy – he backed the approach, as successive governments have done since.

Several more Fine Gael TDs also took part in the debate that day. Fine Gael TD Seymour Crawford told the house: ‘I will never forget the case in which a relatively young woman in her early 70s and her more elderly husband, both diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, had to be put into a private nursing home as no other accommodation was made available for them.

‘All their family members were married with their own family structures to maintain, leaving them in an extremely difficult position as the cost of care came to €900 a week for each parent.’

And he spoke of a ‘close friend’ who was placed by the health authorities in a private nursing home ‘because no other bed was available’. ‘Her old-age pension was part of the funding to that home. Her neighbour who went into a public nursing home later, however, received a refund under the refund scheme. No wonder there are legal cases,’ he added.

Cork Fine Gael TD, Michael Creed, also spoke: ‘Insofar as we on this side of the house may have been implicated in the denial of those rights, I wish to apologise personally to people who were adversely affected. The Ombudsman’s report clearly states that there was a denial of entitlement.’

Mayo TD Michael Ring spoke out on behalf of the people who, he said, had been ‘badly let down’ by the State. ‘People have been hard done by and there are many cases in the Four Courts awaiting adjudication. I cannot understand why these have not been adjudicated on by now. Some cases have been settled and we should know what ones have been settled and why. Many feel injustice was done.’

However, perhaps the best summation delivered in the Dáil over the years came from Ms Harney. It was delivered in 2005 – five years before she clashed with the Ombudsman and refused to supply details about settlements in longstay cases.

‘Over 300,000 people were charged illegally during 28 years,’ she said.

‘This was entirely wrong. They were old, they were poor, they suffered from mental illness, they had intellectual disabilities, they were physically disabled. As vulnerable people, they were especially entitled to the protection of the law and to legal clarity about their situation We are a society ruled by law. No one and no organisation can dispense with or alter a law.

‘If one long-term bed occupant had a lawyer who could help him or her to take a case, he or she would no longer be charged while somebody not so fortunate in the bed beside him or her was charged in all those years,’ she told her fellow TDs.

‘Besides the legal issues involved here, there are significant inequality issues that are unacceptable.’

Timeline of State’s 50-year care-charging scandal

- 1970 The Health Act 1970 is passed, entitling all to free long-stay care services in public institutions.

- 1975 A High Court judgment finds a patient had been unjustly charged. This prompts the Department of Health to consider ways of maintaining charges as an important source of income.

- 1976 The Department makes new ministerial regulations, and issues circular to health boards telling them they

- REPORT: Former Ombudsman O’Reilly can continue to charge.

- 1978 The Eastern Health Board provides the Department with legal opinions showing that the charges are not legally sound. The Department continues to advise health boards to settle out of court when individuals challenge charges. This becomes the default position for decades.

- 1979 The legal adviser to the Department again expresses the view that charges are not legally sound and new legislation will be required. His advice is ignored.

- 1982 A Department review finds there is ‘no legal basis’ for charges. No action is taken.

- 1987 The Fianna Fáil government drafts a Bill which would have made charges legal. The proposed law is dropped.

- 1989 The Commission on Health Funding urges that the law be revised. No such change occurs.

- 1991 Minister for Health, Mary O’Rourke, announces a review of charges which recommends new legislation to achieve legal clarity regarding charges. Nothing happens.

- 1994 Health minister Brendan Howlin publishes a new health strategy which recognises the longstay charges legislation as ‘inadequate’. New legislation is promised. This does not materialise.

- 2001 The Ombudsman highlights how successive governments have failed to rectify the basis for illegal charges. Health Minister Micheál Martin extends free medical cards by legislation to all over-70s. Because more people are now entitled to free care – and because illegal charges continue regardless – this exacerbates the problem.

- 2002 The South Eastern Health Board, facing a number of cases, forwards legal advice from senior counsel to the effect that charges remain unjustifiable. A draft Bill to address the issue is prepared but does not proceed.

- 2003 A Human Rights Commission report once again details the inadequate legal grounds upon which charges are being levied.

- 2004 Mary Harney becomes health minister and requests advice from the attorney general about the validity of charges. She then quickly passes a Bill to retrospectively make the historical charges legal, thereby preventing anyone from suing for recompense. President Mary McAleese refuses to sign the Bill which is referred to the Supreme Court.

- 2005 The Supreme Court rules that people who had paid unlawful charges – or their descendants – were entitled to recover monies. A report into the charging scandal, commissioned by Mary Harney, is published.

- The report highlights ‘systemic corporate failure within the Department of Health for almost 30 years’.

- 2006 The Health Repayment Scheme is established to compensate those medical card patients still living and the estates of those who had died on or after December 9, 1988.

- Patients forced into funding their own private care for the lack of a public place were also excluded.

- Hundreds of thousands of families affected are excluded by these limitations as €477m is paid out to 20,000 families.

- 2009 The Fair Deal Scheme – which finally put charges on a legal basis – becomes law.

- 2010 Hundreds of families, excluded from the compensation scheme, seek to sue the State.

- Ombudsman Emily O’Reilly publishes a damning report based on more than 1,000 complaints from those improperly charged.

- 2011 Faced with a potential liability of €12bn, new Health Minister James Reilly circulates a top secret memorandum.

- Based on advice from

- Attorney General Máire Whelan, the government, knowing it cannot win any case, adopts a confidential containment policy of secretly settling cases to prevent more claimants coming forward. The policy is successful and cases begin to dwindle.

- 2016 The secret strategy continues as Health Minister Leo Varadkar is replaced by Simon Harris.

- 2017 Health minister Simon Harris and Junior Health Minister Helen McEntee receive a confidential update. With no new cases emerging, the containment strategy is reaffirmed again. ‘The current approach is working well litigation is being managed successfully,’ the brief reads.

FURTHER COVERAGE;