By Michael O’Farrell – Investigations Editor.

CORK’S 1956 polio epidemic began on June 13 with a single case reported to the medical authorities.

Cork’s Evening Echo reported two more cases six days later and by July 3, six were infected – a number equal to all the cases for the pervious year.

The outbreak – which largely struck down young children in the south of the city – would go on to infect 500 people nationally leaving many with severe disability and costing 20 lives.

There are still many today living with the scars of their 1950s battle with polio.

At the beginning of the outbreak a worse death toll had been feared. The previous outbreak in Ireland – in 1942 – was still a recent memory and had seen death rates top 27 per cent.

Then, as now, a single figurehead became the person to whom the press looked for updates.

Today Dr Tony Holohan gives daily updates of the coronavirus pandemic from the Department of Health in Dublin.

In 1956, Dr JC Saunders was Cork city’s Medical Officer of Health (MOH). He told the newspapers in the first week of July that ‘an epidemic was imminent’.

By the following week the first victim – a five-year-old girl – passed away and a rising sense of peril spread throughout the country rising to blind panic at times.

Red Cross nurses were put on standby and supplies of iron lungs were bolstered. The public health measures implemented by Dr Saunders and his team will be familiar to many today.

Public swimming baths were closed, bathing in the River Lee was banned, scouting trips were cancelled, young children were banned from cinemas, schools postponed the commencement of the new term in the autumn and Cork students attending colleges in Dublin were asked to delay their return.

The newspapers also printed advice and precautions aimed at limiting the spread of infection.

Unnecessary operations ‘such as extractions of teeth and tonsils’ should be cancelled the Irish Independent reported on July 25.

The advice urged the elimination of flies as much as possible and the avoidance of over exertion and gatherings by children who were most susceptible to the disease.

Many isolated their children completely. ‘My children have been confined to their own garden, deprived of the company of even their usual playmates, during the past three months,’ one reader wrote to the Evening Echo in September.

‘Don’t let your children play too much, feed them well and get them to bed early,’ was the advice of Health Minister Thomas O’Higgins who visited Cork on July 27 to meet the city’s health chiefs.

Mr O’Higgins tried to calm the rising panic saying there was no need for public alarm, no need for mass exodus of children form the city and no need for tourists not to visit Cork.

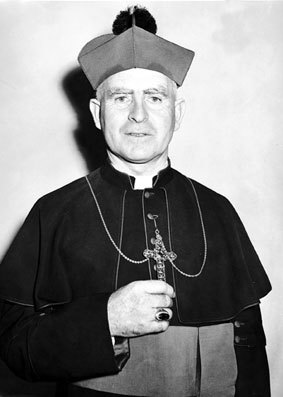

That same day the Bishop of Cork, the most Reverend Dr Cornelius Lucey, decreed that Satur-day July 28 be ‘set aside as a special day of prayer throughout Cork city… for the abatement of the polio epidemic.’

The bishop’s and minister’s appeals had little effect.

By early August the epidemic was still worsening and the behaviour of some was becoming unreasonable.

One aspect of this manifested itself in fake news and wild conspiracy theories.

At one point the authorities had to publish statements in the newspapers to quell a dangerous rumour that there was a link between polio and pasteurised milk.

Soon unwarranted fears were affecting all aspects of life – including international trade.

An August 29, The Irish Press reported that 190 Liverpool dockers had refused to discharge cargo from the Glengariff which had sailed from Cork.

Even after a letter let was read to the men confirming that the ship was free of infection – they persisted in seeking a further guarantee of compensation if they contracted the disease.

Sport suffered too. The Munster Football Association announced a halt to all junior and minor soccer and the beginning of the rugby season was delayed.

The Cork Examiner reported the cancellation of the tennis international between Ireland and Wales scheduled for the end of August at the city’s Sunday’s Well lawn tennis club.

Cricket too was impacted with a scheduled mid-August match between Tramore and Cork Wanderers cancelled.

‘It was felt that the Cork side should not be invited to travel in view of the polio epidemic,’ The Muster Express reported.

By September, with Cork schools still closed, the reluctance of other counties to entertain people from Cork in their midst was not being expressed so diplomatically.

The Mayo camogie team were due to play Cork in the All-Ireland semifinal on Sunday, September 16 in final Castlebar.

But after an emergency meeting, the Mayo County Camogie Board made an ultimatum to Central Council – postpone the game or we won’t play.

The unsporting gesture came amid news of Mayo parents refusing to let their daughters play and reported threats from Castlebar Urban Council that it was prepared to prevent the Cork camogie team from entering ‘within the unspoilt precincts of the town’.

GAA HQ stood firm and, when the game did not go ahead, awarded the points to Cork.

Dublin took a similar step and moved to have Cork fans restricted from entering Croke Park. On August 1, the Dublin newspapers reported an appeal by Dublin’s Medical Officer of Health, Dr JB O’Regan, to the Cork County Board.

The Dublin authorities did not want children from the Rebel County to attend the Cork-Kildare All-Ireland football semi-final at Croke Park the following week.

This led to complaints to the Department of Health from those who wanted to let Cork ‘keep their polio and not infect our clean city’.

One complaint urged the Minister to ‘wake up and do something before polio of the Corkonians is laid upon us’.

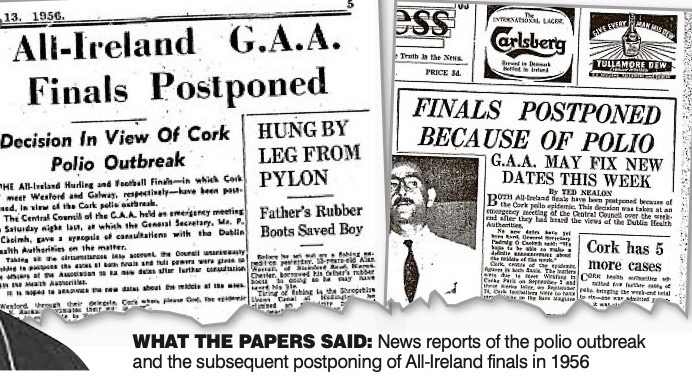

The match went ahead with Cork winning a place against Galway in the final – but amidst the furore that ensued, the All-Ireland final was postponed.

The hurling final in which Cork, led by the legendary Christy Ring, were due to play Wexford, was also pulled.

‘We are very sorry to have to postpone the match but it was a national duty,’ GAA General Secretary, Pádraig Ó Caoimh, told the papers.

Mr Ó Caoimh added that the pros-pect of 20,000 people travelling from Cork was too much of a health risk.

The move was welcomed by Dublin Corporation with The Irish Press reporting that Senator JJ Tunney said he was ‘pleased to note’ the decision.

In reality the outbreak was already beginning to slow at this point with Cork’s Medical Officer of Health, Dr Saunders, telling The Irish Press on August 13 that the epidemic appeared to be ‘lessening in virulence.’

That same day The Cork Examiner reported 126 confirmed cases being treated at Cork’s St Finbarr’s Hospital – one of three dedicated polio facilities maintained at the time in Ireland.

On August 22, Dr Saunders and his deputy, Dr PF Fitzpatrick, addressed the members of Cork Corporation as reported by the Evening Echo.

‘We are slowly passing through the peak period,’ Dr Fitzpatrick told the meeting. ‘It is certainly a great ease to know that no matter what turn this epidemic may now take we are fully capable of dealing with it,’ Dr Saunders said.

‘It is an unfortunate fact that at one stage a spirit of panic should people for which there was no justification. It has been a trying experience for everyone concerned,’

Dr Saunders continued. ‘I feel for the staff of St Finbarr’s hospital. Doctors, sisters and nurses who have been in the frontline from the beginning. No words of mine could express the patience, courage and fortitude of these persons who have pursued their task of tending their patients and nursing them back to health irrespective of the risks to which they were exposed.’

By the end of September, the panic had subsided. The All-Ireland finals proceeded with Cork losing both.