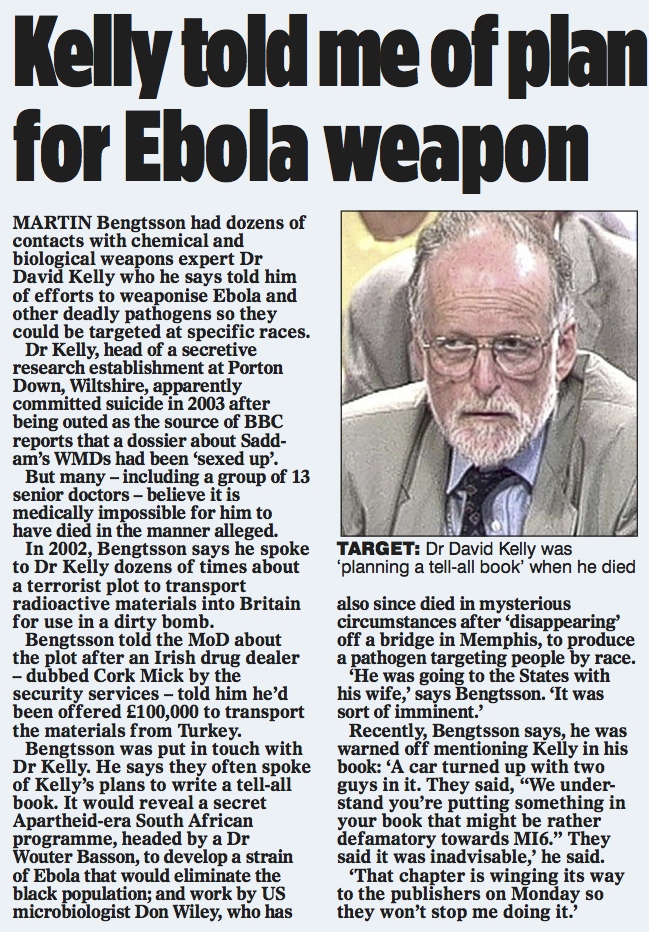

Michael O’Farrell

Investigations Editor

At the end of a narrow, muddy trail deep in the Galtee mountains lies the home of 83-year-old Martin Bengtsson – a former spy, smuggler, gun runner and self-confessed killer.

Though he now lives as a hermit and artist amidst dozens of dogs, cats and a pet Tarantula, there remains a sharp whiff of cordite about his personna.

At the property’s edge a crude, red-lettered sign pinned to a tree contains an ominous warning. ‘Trespassers will not be prosecuted,’ it reads. ‘Their next of kin will be informed.’

For those who missed the meaning of the first warning another sign a few meters further on is more to the point.

‘If you can read this you are within range,’ it warns.

Beyond that, perched on the edge of a steep slope sits Mr Bengtsson’s home – a small, dishevelled Hobby Prestige caravan.

Behind that again is another, smaller caravan occupied solely by cats against which a waist high pile of dark rum and brandy bottles is steadily inching towards the sky.

In an old farm yard below the caravans an untamed horse is homed while a tin-roofed three bedroom house overlooking the yard is entirely occupied by dogs.

Inside his home, listening to Mozart’s 4th Violin Quartet and supping brandy from a tumbler, Mr Bengtsson reveals himself to be a fascinating and unique hybrid of a character.

’17 years I’ve been up on top of this mountain – and I love it,’ he says smoothing out his red Gucci neck scarf.

‘I drink two bottles of brandy a week and four bottles of vino. I eat well. And I occasionally get me leg over so there’s nothing much wrong with my life,’ he chuckles.

One moment he’s a deadpan comic imparting his father’s advice (‘Never go to bed with a woman you’d be ashamed having breakfast with. I try to adhere to this but it’s cost me a lot of bacon and eggs.)

And the next he’s matter-of-factly saying things like; ‘Did I tell you I was employed by the FBI to knock off a bloke called Leroy Eldridge Cleaver?’

To the uninitiated, the FBI line could easily be mistaken for a joke or a fantasy were it not for the fact that it is in fact largely true.

What actually happened, as described in his published autobiography, was that Mr Bengtsson was sprung from jail in Gibralter where he was awaiting an assault charge and utilised by US agents to captain a yacht on a secret mission.

That mission involved setting an elaborate trap – a kinky on board sex party – to lure Clever from hiding in Algeria where he had absconded in 1972 after his Black Panther members hijacked a Florida airliner and ransomed it for a $1m.

Because the daring plan, which later made for lurid newspaper headlines when it became public, was abandoned at the last minute the tale is perhaps one of the least dramatic stories that Mr Bengtsson has to impart.

Yet he nevertheless wound up being charged for gunrunning when he absentmindedly left his fee – the yacht and any weapons it happened to contain – tied up in France over Christmas.

Such memoirs are astounding by any measure but by and large each Bengtsson story – through his time as a cigarette smuggler for the Italian Mafia, a gun runner for an assortment of regimes, a stuntman on spaghetti westerns, an explosives and demolitions expert and a forger of famous artworks – is backed up with records, documents and photos.

Other papers, letters and newspaper clippings back up further adventures notched up while working for spy agencies such as the CIA, MI6 and the MoD.

These are stuffed into files and folders often found underneath Sid – a striking ginger tom cat who reminds Mr Bengtsson of a one-time Mafia colleague (Sydney Downer) who died during a shoot out at sea in the early 1950s.

It was on this occasion when Mr Bengtsson killed for the first time.

‘I shot the bastard first – I pulled faster than he did,’ he shrugs describing a gripping face-off aboard a sinking, enflamed yacht crammed with Mafia contraband.

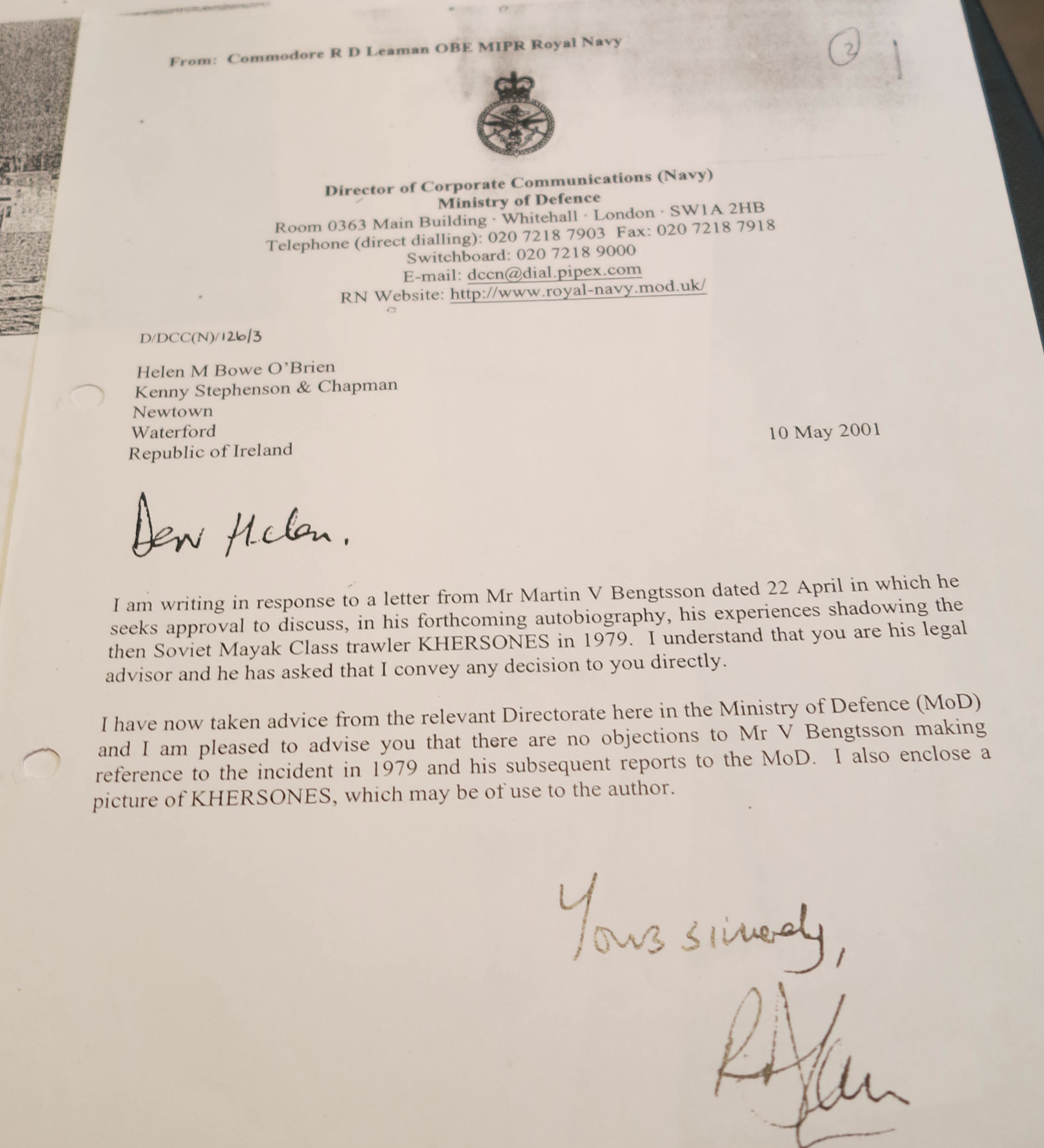

The files contain some extraordinary documents – not least a letter form the MoD authorising Mr Bengtsson to disclose the Cold War role he played in shadowing a Soviet spy ship from the shores of Plymoth to the Baltic in 1979.

Describing his life Mr Bengtsson repeatedly returns to three passions – art, music and women.

‘It wasn’t so much the women in my life that made me who I am,’ goes one of his favoured lines. ‘It was more likely to be the life in my women.’

But it’s actually a lifelong dedication to seafaring activities that contributed most to the decades of subterfuge, intrigue and mayhem he has known.

Were it not for his skill as a sailor he’d never have wound up transporting contraband and weapons, captaining a yacht for the security services, or tailing Soviet spy ships.

And were it not for the contacts he made during these missions he’d never have become a bodyguard to the likes of Prince Bandar bin Sultan in the 1980s when he was Ambassador to the US.

A key and controversial associate of Presidents Bush snr and jnr, Bandar would later become the chief of the Saudi Intelligence Agency stepping down only in April this year.

Nor would he have found himself seated opposite the recently exiled Sultan of Zanzibar in 1964 whose grip on power had just been seized by a revolution backed by the Communist bloc powers of China, East Germany and the Soviet Union.

‘Zanzibar got invaded by the Chinese and they wanted to take it back and they asked me if I could get mercenaries and weapons,’ Mr Bengtsson explained matter-of-factly handing over the subsequent letter in which the Sultan’s team outlined their needs.

‘We would be very grateful if you would provide us with the following information as soon as possible, the correspondence reads before going on to ask for the prices of ‘Sten guns, Bren guns, rifles 303 Mark 4, rifles SLR, suitable anti aircraft weapons and hand grenades.’

Also on file is a letter from the Scottish arms dealer Mr Bengtsson approached to procure the necessary mercenaries for the job.

‘We would particularly like to know the type of weapons you have at your disposal as a number of people have mentioned that they are experienced in certain categories,’ it reads.

Bengtsson succeeded in procuring the weapons and fighters all of which were positioned in Mombasa ready for the attempted coup. But an ill-advised attempt by an official to secretly secure further support in Zanzibar in advance of the attack backfired leading to the plan being called off.

Another gun running task – this time in exchange for a fist full of diamonds from an African General – involved shipping weapons from the UK to a delivery point up the Congo river before flying home.

Throughout his exploits Mr Bengtsson nurtured a love for art inherited from is father and in time began to copy some of the great masters himself.

Inevitably this led to a journalist friend challenging him to fool the experts – a ploy which culminated in the appraisers on the Antiques Road Show programme being completely conned.

You know the Antiques Road Show? Well I screwed them,’ he says gleefully. ‘The chief valuer valued three of my paintings as turn of the century masterpieces.’

In 1999 M rBengtsson moved to his present home. ‘I wanted to get away from all the rat race and everything else I’d been mixed up in’ he says.

‘I don’t go anywhere. And from what I see of the world outside – with what’s going on a the moment – I don’t think I’m missing very much.’

But his past and his unique talents did not go unnoticed.

Soon after settling in he was approached by members of Martin – the General – Cahill’s gang with a damaged painting from their 1986 robbery of the Bait collection at Russborough House in Co Wicklow.

‘It was damaged so I did it up. I didn’t meet him it was ages after he died. Somebody brought the thing to me and said could I repair it so I did.’

Mr Bengtsson says the painting a townscape by Italian artist Franceso Guardi needed little work. ‘I just put in the tree and the clouds in the corner, that’s all. It only took an hour and I got £500.’

Although he appears effortlessly good humoured and witty there are some topics which bring Mr Bengtsson to tears.

One such story will be included in a second book about his exploits which has just been submitted to publishers involves a teenage prostitute he once rescued from Mombasa.

‘In a bar this girl came over and she could not have been older than 12 or 13 and she said ‘you want fuck fuck?’ he remembers.

‘I knew it went on but it horrified me and I was drunk – pretty drunk. I fished in my pocket and I had two five pound notes in there and I gave them to her and I said go home and she did.’

But the largesse had made an impression on the girl’s parents who turned up the next morning begging Mr Bengtsson to smuggle her to the UK.

‘You good man – you take girl to England. Get her on your ship to England. She die here,’ they said.

Nine weeks later as his vessel docked back home, a contact in a convent arranged for the girl to be brought to safety.

‘I don’t know why but it always upsets me for some reason,’ Mr Bengtsson explains as he begins to sob almost uncontrollably in his caravan.

As he tells it the nuns surprised him at home one day a decade later.

‘They brought this absolutely beautiful girl and she got out of the car and she flung her arms around me and said; ‘you saved my life.’

‘I said ‘no I didn’t – I gave you a free ride on a ferry boat. She turned into a lovely girl – a librarian – and she played guitar. She taught me a song called Malaika – it means angel in Swahili.

Later he places a phone call with a request about this article. ‘Dont make me look like an angel, he asks. ‘Cause I have been a bastard most of the time.’

However he may be judged Mr Bengtsson, though defiant and admirably healthy, knows his days are numbered.

‘I had a small stroke but it’s fine. I just have to be careful when I drink because sometimes it runs down the side of my mouth,’ he says as he swirls his brandy, staring down at the glass.

And when it happens he knows precisely how he wants to go.

‘I want a Viking send off – a quick singe on top of a pile of motor tyres and let the wind sprinkle me where my pets are buried to the tune of Shostakovich’s Gadfly Suite,’ he says.

‘Wherever you go when you die – that’s the best music to take you there.’

HOW MARTIN BENGTSSON WOUND UP TRACING A SOVIET SPY SHIP FOR THE MOD.

We’ve got one of Ivan’s off the coast’ Martin Bengtsson radioed his handler at the MoD. ‘ What should I do?’

‘Follow!’ came the curt instruction from HQ between bursts of static.

It was the autumn of 1979, the year the Soviets invaded Afghanistan and Margaret Thatcher came to power – two events that significantly hardened anti-Communist resolve in Britain and the US where Ronald Regan would become President the following year.

Mr Bengtsson though was between jobs – passing time delivering yachts for wealthy clients while discreetly keeping an eye on any suspicious shipping movements that came his way for his acquaintances at the MoD and in MI6.

‘People would buy a boat and either they hadn’t got time or the bottle to take it out through Biscay to the Mediterranean and they’d want it down there for next year’s summer holidays. So I was positioning yachts for people. One after another.’

But the ship Mr Bengtsson had just stumbled across – just far enough from shore to be in international waters, was no ordinary yacht.

‘I’d been in the Royal Navy as well and it wasn’t difficult to identify a Russian spy ship if you saw one,’ he recalled. ‘She was anchored up off the coast of Plymoth.’

Using a think blanket of fog as cover the Soviet Mayak Class trawler, Khersones, had edged as close as possible to shore – apparently to plant or retrieve a sea bed listening or interception device.

‘They were pulling up something like a giant cotton reel, some listening gear. And they had a tarpaulin over her covering her name up. As we followed around the wind blew it up and we could make out the name.

Part of a specialised Russian fleet of electronic eavesdropping vessels in use at the time the Khersones was fitted out with the very latest in electronic interception equipment allowing it to suck up all manner of communications as it lay in the shadows off the British coast.

Now that it had been rumbled a bizarre game of cat and mouse ensued – one of many such instances on all sides throughout the Cold War.

‘The weather was very foggy and somehow between Folkestonne and Dover in the morning I caught them up and passed them and I pulled up almost along side them.’

‘They shouted out ‘have you had your breakfast?’ And they threw a heaving line across with something tied on the end of it. I thought – watch it – it’s a bomb on the end of that.’

But it wasn’t. Instead it was a bottle of Vodka.

‘They actually invited us on board the Russian ship for Breakfast which we didn’t accept of course.’

‘But we followed them until they just entered the Baltic – they were going home and that was it. We came back.’